How Do Viruses Work?

Get answers to:

- How do viruses get into cells?

- Do some viruses "hide" in the body?

- Can viruses rewrite DNA?

There are five things a virus can do:

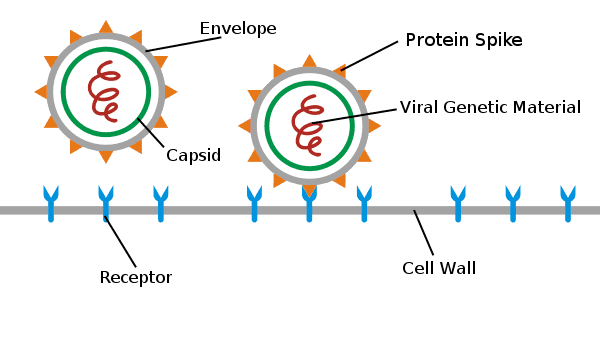

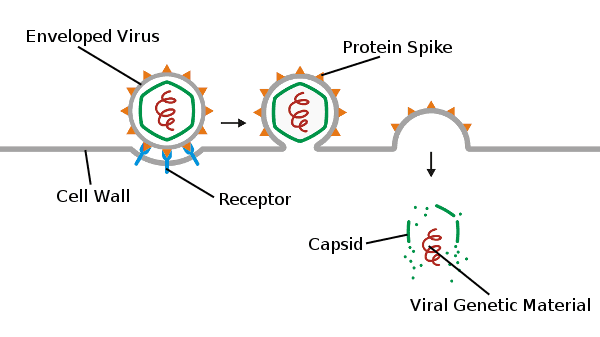

Attachment

Before anything, a virus needs to acquire a host cell. Since viruses are not alive – they are inert particles – they cannot “seek out” cells to infect. They are at the whim of whatever medium they are being transported in.

All viruses have “sticky” parts that bind (stick) to particular parts of cell walls. Most often, this is a protein “spike”.

It is a random process and the virus has to “bump” into the appropriate cell to attach.

Entry

Once attached to a cell wall, the next step is the entry of the viral genetic material. There are a number of different ways this can happen:

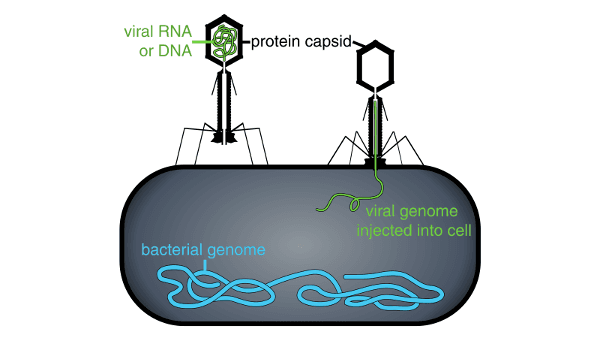

Injection

This happens with complex viruses that infect bacteria. When the virus attaches to the bacterial cell wall, the genetic material is “injected” into the bacterium. Depending on the virus, this is done by either extending a protein tube through the cell wall, or by attaching to a pore and injecting the genetic material through the pore.

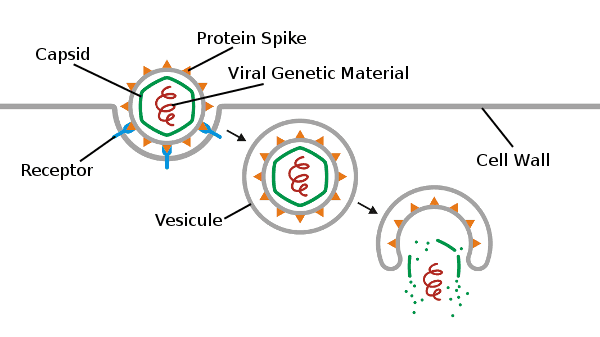

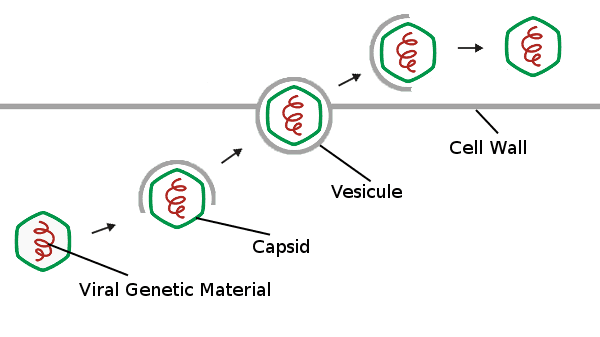

Endocytosis

The cell wall engulfs the virus, forming a vesicle,1 and brings it inside the cell. Once inside, the virus and capsid are released, the capsid dissolves, and the viral genetic material is released. Naked and enveloped viruses may enter via endocytosis.

Fusion

Only enveloped viruses can enter by fusion. The viral envelope fuses with the cell membrane and the virus and capsid enter the cell. Once inside, the capsid dissolves and the viral genetic material is released.

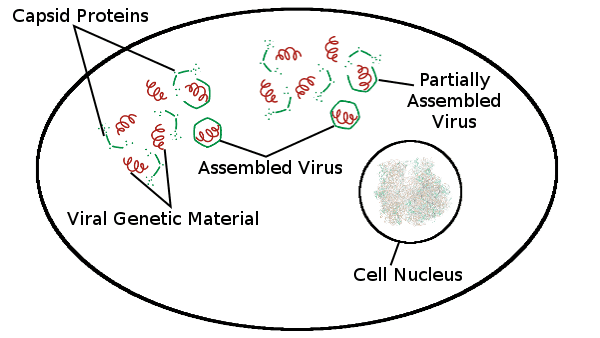

Replication

Once the viral genetic material is inside the cell, the cell’s machinery begins to replicate the viral proteins and enzymes. The viral enzymes are necessary because most of the virus cannot be replicated using the cell’s machinery – the cell’s native machinery cannot read most of the virus’ genetic code. The viral enzymes are what allow the virus to replicate.

As the various viral parts are manufactured, they self-assemble into new virus particles.

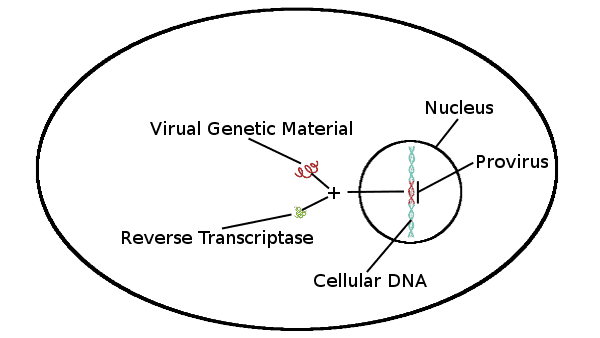

A special class of viruses known as retroviruses also produce an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase. This enzyme copies the virus’ genetic material into the DNA of the cell. Retroviruses rewrite the DNA of the cells they infect. These viruses spread with each cell division. When a retrovirus has copied itself into the DNA it is known as a provirus. Retroviruses replicate like other viruses, but they can also go dormant and hide in the DNA of the cell.

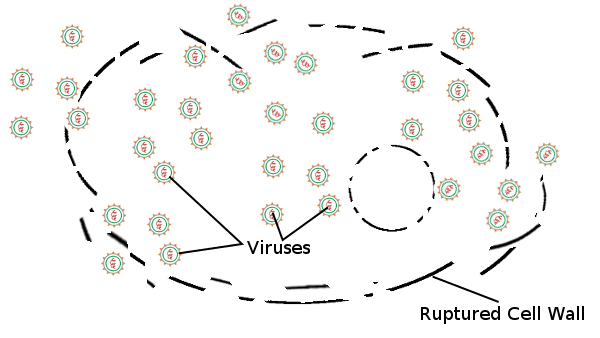

Shedding

If a virus was simply contained to the cell, it wouldn’t pose much danger. It is the replication and later spreading that causes the problem.

There are three ways that viruses exit the cell and spread to other cells:

Apoptosis

The cell dies and disintegrates. Most non-enveloped viruses are shed this way. The cell may die because virus replication has used up all its resources, or it has been marked as infected and destroyed by the body’s immune system. HIV (which is an enveloped virus) uses this method to infect macrophages.2

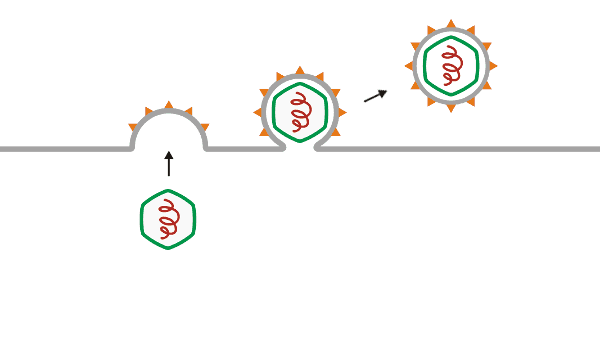

Budding

The virus pushes its way through the cell membrane and acquires a lipid envelope from the cell membrane. This gradually uses up the cell membrane. If sufficient cell membrane is used up, it may result in cell death.

Exocytosis

This is the opposite of endocytosis. The virus inside the cell is wrapped in a vesicle and transported to the outside of the cell wall. Once outside, the vesicle breaks down and the virus is free to infect another cell. This is mostly used by naked viruses, although some enveloped viruses use this mechanism as well.

Latency

Some viruses, may shut down or become dormant after the initial infection and reproduction cycle. Non-retroviruses remain in the cytoplasm of the host cells. Proviruses remain in the DNA of the cell and subsequent daughter cells.

These viruses may reactivate when certain stress conditions are reached.